The following was presented in 2005 at the UPLI Congress in Tai an, Shandong Province, China, by Gisela Köpp:

The Music of the Language: Found and Lost in Poems

The birth of a poem happens in silence in a creative process. As the result of the sensitive work of mind and soul, thoughts and images merge. But soon the silence will be broken. We want to hear what we created, although we first write down, what comes to our mind. We will hear the music of our language and the sound of our voice. The action of the human voice will turn every word into a musical experience and the breathing rhythm gives truly life to the poem. Phonetic and linguistic research will have another perspective.

Words are the body of literature. Vibrant with life we will perceive the poem as art. The music of the language is audible in its vowels. In addition, the exhaling part of the breathing rhythm creates the different consonants, which structure the language in a most differentiated way.

Allow me to give some examples in German, my mother tongue, in comparison to the English translation, to let you experience the music which is very different in its translation.

Look and listen to the vowels. You will sense the difference between the vowels. After the already different prononciations of the o in offene and open you also can experience the different flow of the breath in f (even two) and in p. F has the flow of the breathing air and the p lets the air suddenly go off, like a small explosion. The most striking difference in the perception of the next word is the vowel, the music in this word Blüte: ü , the English language does not have this vowel at all, the English expresses Blüte as blossom, to differently sounding o. If you prolong the vowel with your voice, you will perceive the difference even better.

In the second line of this poem you experience in addition the different rhythm: short long (emphasised), short short long (emphasised), short. In the translation: Short (emphasised) short (also emphasised).

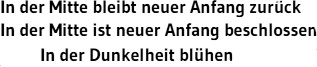

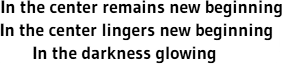

In the next line the word Mitte turns into center, Anfang into beginning. The musical sound i turns into the less sounding e. A in the German original comes twice, truly the start of the alphabet in both languages but sounding differently. The English word in the poem starts with the b without voice followed with the vowel i, twice:

In this last line I again want to focus on the vowels of Dunkelheit und blühen. You will find extreme differences between the vowels of the original and the vowels of the translation. U in Dunkelheit and a in darkness. I cannot avoid to make even a daring, far reaching comment: With the German word Dunkelheit the u sounds dark and is actually the darkest sounding vowel of the German language. So the darkness stays dark, the English translation expresses with the music of the a sound already that it will not stay dark. There is already hope expressed to be „happy“ again. Darkness is not an endless tunnel. There is light at the end of the dark tunnel.

Look at and listen to Blüte again, followed by blühen. Produce the vowel and enjoy the sound with your voice, try the same with blossom and glow.

The different perceptions are obvious and cannot be translated. Therefore I would suggest that always the origional should be available at least in print. If we are only listening, we should not turn away with the comment: „I do not understand“ because you will understand the music and the rhythm, so essential in a poem.

Languages are a challenge and we cannot study all of them. But we can practice to listen to the different sounds and we will understand more of the different shades in which we are able to express ourselves. Dann haben wir Glück, then we have Glück or happiness ? Read the small essay by Hermann Hesse about Glück, only the word as such, one piece of the many in the puzzle of our languages, Glück and happiness, two different sounds, a different music and different shades in the meaning.

Another challenge: Es schienen so golden die Sterne, the first sentence of Joseph von Eichendorff’s poem Sehnsucht – Longing, in translation: The golden stars were shining. Unfortunately, the long sounding i is lost and the poetic beginning turns just into a correct statement, also the rhythm is a very different one.

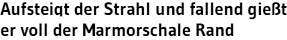

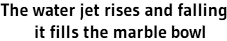

Another example: In this case the noise of the breath within the consonants is meaningful music. We find in the first sentence of a poem by Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, Der römische Brunnen (The Roman Fountain) the consonant f. It is the f in the first word in German which gives already the essential sound of a picture where the water fountain rises and falls: Au f s t eigt…. the consonants express the flow of running water, we create this consonant with a structured, controlled exhaling – being creative with the breathing rhythm given by nature to us.

I would like to emphasize the human breath and the sound of the voice as a given phenomenon, no matter who creates it and for what purpose. This has to be taken into consideration and fully understood before we can venture into translation. When we want to translate poems into another language, the music of the language will change. It will sometimes change in such a dramatic way that it affects the meaning of the words and takes away a certain truth. We only can try to create a translation that sometimes leaves a secret between the lines.

Whether we write or recite poems, we have to listen to more changes than the content provides and we have, particularly in international exchange, to listen to the music of the poem (and I call it deliberately music, not only sound). Since music and rhythm mostly is lost in translation, we never can fully appreciate the art work. We do not only speak different languages around the globe, we also sense certain things differently and even think along different ways, which does not mean that we cannot come to the same conclusion.

We are guests in a country whose spoken language has such an incredible wealth of so many shades of tones to convey even more differentiated meanings. In translation, as I stated before, we loose many essential turns in a poem. Only if we take music and rhythm of each language seriously, we can understand the complexity of the poem. Then it will open its core to let us understand the whole with its true meaning.

In Lahore, Pakistan, I listened once for two hours to a group of revered elderly gentlemen reciting poetry in Urdu. I was fascinated and could not turn away. I understood what was created by breath and voice. It was the music with its rhythm given by another language. While listening I sensed the soul as a golden thread, guiding the listener to the core of what they wanted to say.

Once I asked a student who came for singing lessons whether she could recite some poetry in her mother tongue. She said that she loves poetry and prepared some Haikus for me. After the first Haiku I asked her to repeat it, her voice was not fully in action. I said to her: ”Before you start, why don’t you think of the ocean, the horizon as far as you can see.” She repeated the poem and I was delighted. “You speak Japanese?” she asked. “I do not speak the language,” I said and she translated for me the first line of this Haiku letting me know that the first line spoke of the ocean and the horizon. I had perceived the exact image.

International exchange cannot really happen if we do not allow time to learn more about the music hidden especially in poems. Another horizon beyond intellectual understanding will open up. Music does not only come to a poem when a composer sets the words to a specific melody, creates songs and lieder. It is already

inherent in the words. We consider music as t h e international language. Unfortunately, we listen seldom to the music of our languages. We rarely consider ourselves as human beings with an instrument to create music also while s p e a k i n g.

A poem radiates in many different ways. I would like to remind you of ein Feld der Stille (a field of stillness) around a poem, to hear its music better. When you look into a book of poems, you see it: All this white space around a single poem. Take it into consideration, so that the poem can expand and the value does not diminish. One day we will understand Stephan Mallarmé, who said: “The perfect poem would be the silent poem in pure white.” A poem deserves breathing space, so essential for peace.

One short poem by myself as an example to show that it can happen that we create the same music for one word in German and in English, although with different vowels, meaning in different ways. But the conclusion of this poem has the same “music”. But in another essential word for this poem we sense the atmosphere quite differently and hear very different vowels: It is Dämmerung and twilight.

Blick auf den Grand Canyon

Nichts eingefangen als das Licht des Abends.

Wer kann sagen:

Es werde Licht?

Wer kann empfinden, was Dämmerung ist?

Tröstlicher Übergang,

gewaltige Natur wird sanft,

das menschliche Auge hat sie berührt –

Frieden. (F ausatmen- exhaling, n Lockerheit-relaxation)

View of the Grand Canyon

Nothing captured but the light of the evening.

Who can say:

Let there be light?

Who can comprehend what twilight is?

Comforting transition,

powerful nature becomes gentle,

the human eye has touched it –

Peace. (Starts suddenly with a P more explosive, but also at the end of this word exhaling)

Frieden and Peace have the same music in the most intensive sound i, no matter how we have to write it.

Confucius and, very similarly, Plato emphasized the importance of music in education. Why not think of the benefit of learning the music of the language and not only its grammar, of learning to use the voice as an important instrument given to all for free, to use it as an essential tool to discover poems in a different way and to open the ears for other languages in a musical way. Thus, we could understand a poem, even if there is no translation available. This would put real life into learning a language and communicating with each other.

I looked into different translations of the Tao te King by Laotse into German (Richard Wilhelm and Carl Dallago, at the beginning of the 20th century) and realized that without hearing the text in the original language, we can not even judge which translation is closer to the truth. David Frost said once: ”We dance round in a ring and suppose, but the secret sits in the middle and knows.”

I recently went to the first European Conference of The International Women’s Writing Guild in Geneva and found this poster at the United Nations: Here you can see in a very simple and truly uplifting way the importance of the vowel, which carries the music of one word and turns War into PEACE. (A white dove flies up from War to PEACE, carrying it’s A in its beacon, to leave just W R as an empty word, inserts it into PE CE, to complete the meaning of PEACE.